Belfast, "The Troubles", and the Strong Link to Israel and Palestine

(picture above by Valerie Root Wolpe)

Warning, this will be a long one, with lots of pictures.

How do you describe the complex, ancient, and ongoing - and contradictory - relationships of Belfast and Northern Ireland to one another and those around? The more you know about them, the more astonishing you will find them—very much like the Middle East. And that is why, unsurprisingly, the city, and its surrounding countries of Ireland and the rest of the UK, are so deeply intertwined with Israel and Palestine.

You see Palestinian flags everywhere in the Irish/Republican/Nationalist/Catholic areas, and Israeli flags in the British/Unionist/Loyalist/Protestant areas. The struggle in the Middle East has become a symbolic marker of your position in Northern Ireland (and Ireland, and Britain to a lesser degree).

Where to begin?

Perhaps a glimpse of the craziness is in the Battle of the Boyne; Fought in 1690, still very much remembered and alive here, celebrated every July 12 by Protestant Loyalists in Northern Ireland with a parade including a burning of the Irish flag (see last post). The victory of King William of Orange against, the deposed, King James reinforced Protestant rule in Ireland. Simple, right? A war to maintain Protestant control over Catholicism in Ireland. Except Pope Alexander VIII and the Vatican were allies of, the Protestant, William and an enemy to James, who was fighting to maintain Catholic Irish sovereignty and reinforce religious tolerance for Catholicism! The Vatican shared William’s hostility to (Catholic) Louis XIV of France, who at the time was attempting to establish dominance in Europe and to whom James was an ally. Got that? Every fact about N. Ireland seems equally convoluted.

(Or St. Patrick, the very symbol of Irish nationalism and pride, who was born in Britain.)

Before we get more into it, let me reintroduce and thank the remarkable Gary Mason: a famed mediator and peacemaker of the last many decades, a Methodist Minister who founded Skainos, an organization that brings together the two sides in Northern Ireland, creating a safe, neutral space and providing social services such as a senior center and an integrated school, who now runs the NGO “Rethinking Conflict.” He has been an important part of the reconciliation process in Northern Ireland, and has also been active in the Israeli-Palestinian situation for over a generation, meeting with Israeli and Palestinian leaders in the Middle East as well as hosting groups in Belfast (he just had the ultra-orthodox Shas party leadership here), there, too, bringing the opposing sides together for dialogue.

Gary Mason standing in a gateway marking the division between a Catholic and Protestant area.

Gary Mason standing in a gateway marking the division between a Catholic and Protestant area.

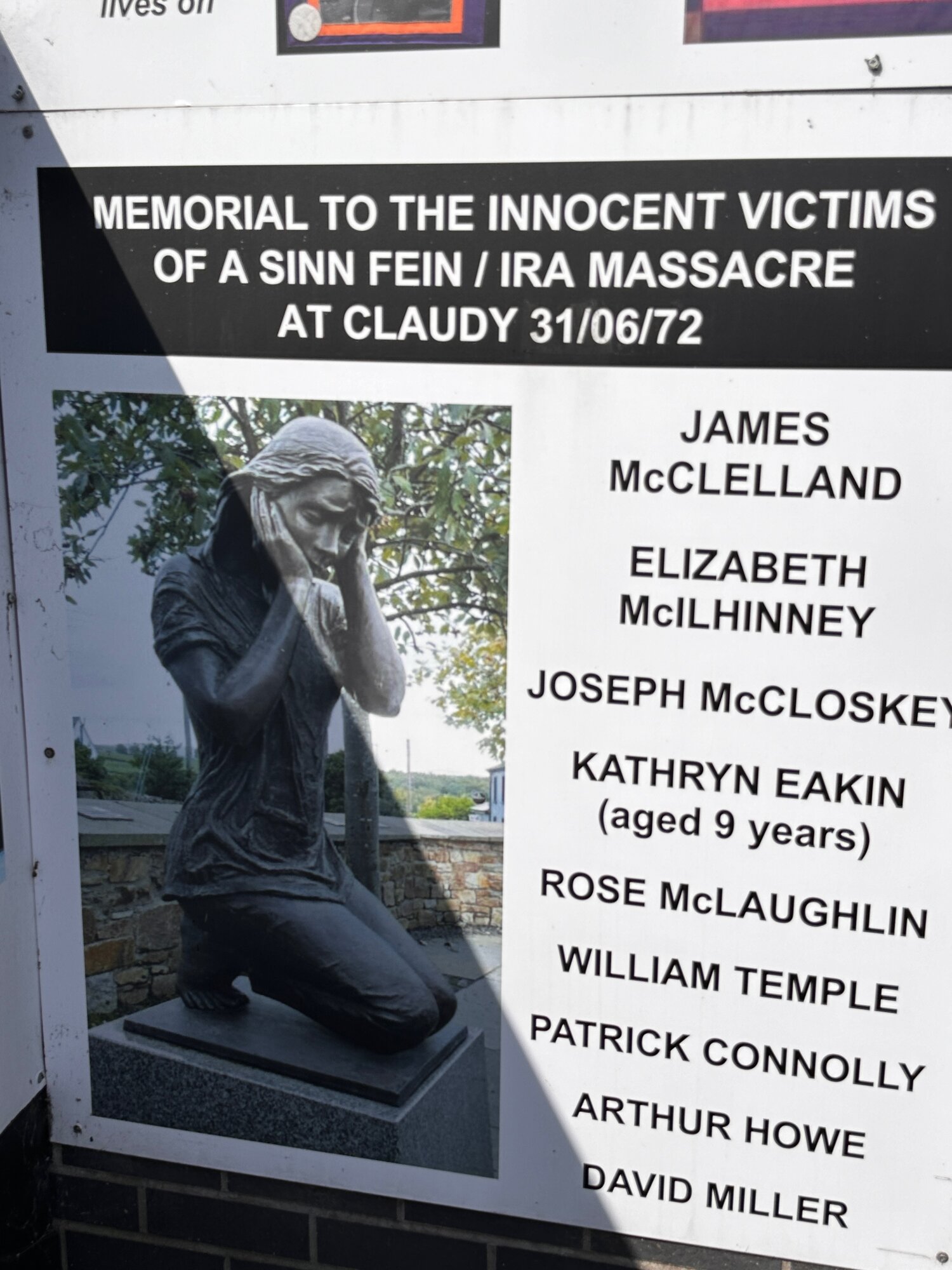

Gary was the best guide one could ask for, unpacking the convoluted history, and the living legacy, of the Troubles. I won’t go through the 30 years of bombings, struggles, and hostilities, leaving over 3600 dead and over 47,000 injured—bombs which hit more innocents than combatants, women and children going about their daily lives—however, except to say both sides still point with outrage to the other’s atrocities while ignoring their own. This is despite the fact that overt hostilities have been stymied for more than a quarter century now. The Good Friday agreement of 1998, as an achievement in conflict resolution, is a landmark in transitioning two implacable foes to a peaceable state of life together. It is clearly a model to be emulated, even while, 25 years later, the simmering resentments persist. (Note: The Sinn Fein was the political, nonviolent - they claimed - armed of the Republican side, and the Irish Republican Army, the IRA, was the military wing.)

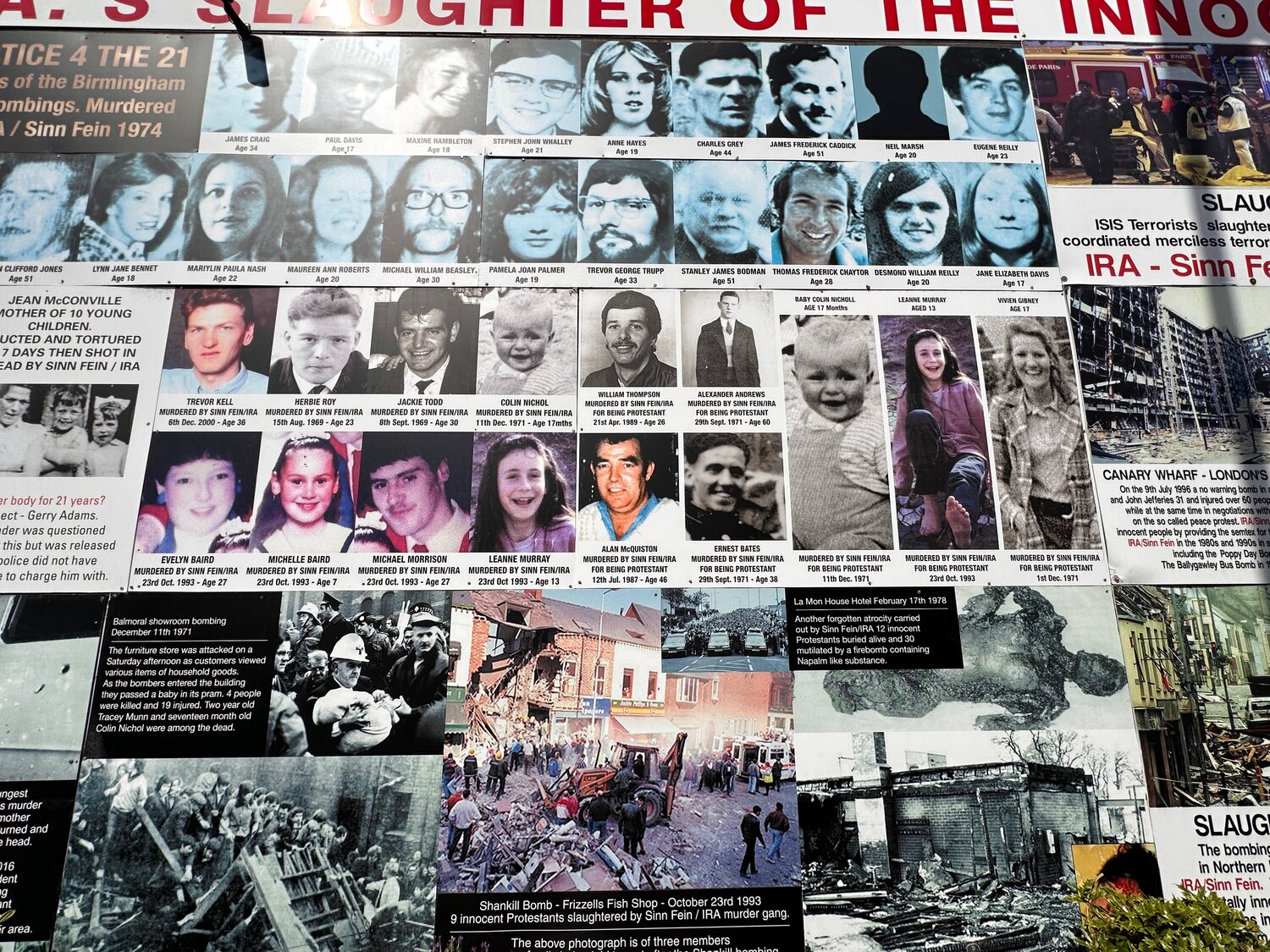

Let’s look at how things are framed. First, Protestant/Loyalist/pro-British areas: You cannot miss the signs anywhere you go (picture above by Valerie Root Wolpe)

You cannot miss the signs anywhere you go (picture above by Valerie Root Wolpe)

These are just a few of the posters and memorials that punctuate almost every street corner in the Protestant areas. Large reminders of IRA terror. To be fair, IRA bombings were more indiscriminate and, ultimately, more destructive than those launched by Protestant militias. Republican (Irish, Catholic) paramilitaries were responsible for some 60% of the deaths, Loyalists (Protestant, British) 30%, and security forces 10%. But numbers alone do not justify the ends, as the Catholic/Republican/pro-Irish-unification neighborhoods also prominently remind us:

A memorial to the Catholic fallen, note the Palestinian flags as well - more on that in a moment

A memorial to the Catholic fallen, note the Palestinian flags as well - more on that in a moment

A Catholic memorial. The symbol on the flagpole is the Irish lily, the Easter lily, a symbol of Irish freedom and remembrance that commemorates combatants who died during the 1916 Easter Rising. The lily’s colors echo the Irish flag.

A Catholic memorial. The symbol on the flagpole is the Irish lily, the Easter lily, a symbol of Irish freedom and remembrance that commemorates combatants who died during the 1916 Easter Rising. The lily’s colors echo the Irish flag.

So these memorials are everywhere, a reminder that, even in peace, even though the Troubles ended in 1998, even as the country as a whole tries to heal, it remains divided. Protestant children go to Protestant schools, Catholic children go to Catholic schools, despite attempts to create and promote integrated* schools, progress is greater in some areas than others. Nationwide only 7% of schools are integrated. The Catholic children hear one version of their nation’s history, the Protestant children another.

*(“integrated” means something different in N. Ireland than in the US)

Walls and fences constructed between neighborhoods during the Troubles, and supposed to be dismantled after the Good Friday agreement, still stand all over Belfast. And both sides seem to want it that way (picture by Valerie Root Wolpe)

Walls and fences constructed between neighborhoods during the Troubles, and supposed to be dismantled after the Good Friday agreement, still stand all over Belfast. And both sides seem to want it that way (picture by Valerie Root Wolpe)

Which brings us to Israel/ Palestine. The Middle East has been symbolically grafted onto the division between the two sides. The PLO helped the Sinn Fein early on, which cemented a relationship—though, a decade or so prior, Ireland was an early supporter of the fledgling state of Israel, since it was fighting the British. The Republicans see a parallel; the Palestinians are fighting an occupation, and so are the Irish. But the depth of it is astonishing. Palestinian flags are everywhere, flying next to Irish flags, and murals in Catholic areas extol the Palestinian struggle. And not only in Northern Ireland, they are common throughout Ireland itself.

Irish prisoner clutching hands with Palestinian prisoner.

Irish prisoner clutching hands with Palestinian prisoner.

On the other side, Israel is symbolic of a realized stable society that has a right to the territory it inhabits, and is seen as the victim of terrorist bombings and an intractable foe:

The Israeli flag on the fence surrounding the tower, with Irish and Palestinian flags adorning the tower to be set on fire and incinerated at midnight, starting the July 12 event.

The Israeli flag on the fence surrounding the tower, with Irish and Palestinian flags adorning the tower to be set on fire and incinerated at midnight, starting the July 12 event.

.jpeg) Stories of solidarity between Ulster Volunteer Force and the Zionist struggle

Stories of solidarity between Ulster Volunteer Force and the Zionist struggle

And so it goes. Yet, despite the posters and the ongoing tensions, islands of hope spring up all around. Take William Mitchell, the founder and builder of ACT, the Action for Community Transformation program. As a young teen, William was recruited by his upbringing and the stories he was told into the Ulster Volunteer Force, and at 15 engaged in a political killing. After 13 years in prison—considered not as a jail by the combatants but as a prisoner of war camp—upon release he began working with at-risk youth in his community, got a Ph.D. studying the young men from the Protestant neighborhoods of his youth, and created ACT. ACT is a museum of the history of the Troubles, balanced and informative, even as it portrays the experiences of Protestant youth.

William Mitchell and me standing in a room in the ACT Museum that replicates the “POW” holding cells he was incarcerated in.

William Mitchell and me standing in a room in the ACT Museum that replicates the “POW” holding cells he was incarcerated in.

Ultimately, the experience of Belfast is one of hope and optimism. The hostilities there seem no more intractable and historical than in the Middle East; after all, I saw a parade celebrating a sectarian victory from 1690! Yet, somehow, after the bombings and the shootings, the deaths of women and children on both sides, seemingly unyielding political ideologies, they found their way to peace. With Gary Mason as a guide, one can see beneath the surface, understand the many historical, religious, cultural, and socioeconomic influences that keep the old narratives alive, even while people like Gary and William try to forge new ones.

For, in the end, it really is about the stories we tell, about how we transmit truths to the next generation, and how tightly we cling to our own version of history and ignore the pain and lived experience of the other. For 25 years, there have been no political killings in Northern Ireland. That is something to celebrate, that is the foundation you need to move forward. It is not surprising that the peacemakers of Northern Ireland see their victory, their hard-won peace, as a possible model for the Middle East.